: The article is dedicated to Griboedov’s ageless, always relevant play “Woe from Wit”, society spoiled by conditional morality and Chatsky, a freedom fighter and a convict of lies that will not disappear from society.

Ivan Goncharov notes the freshness and youthfulness of the play “Woe from Wit”:

She is like a hundred-year-old man, near whom everyone, having outlived their time in turn, is dying and wallowing, and he walks, peppy and fresh, between the graves of the old and the cradles of the new.

Despite the genius of Pushkin, his heroes “turn pale and become a thing of the past,” while Griboedov’s play appeared earlier, but survived them, the author of the article believes. The literate mass immediately dismantled it into quotes, but the play passed this test as well.

“Woe from Wit” is both a picture of morals, and a gallery of living types, and “forever sharp, burning satire.” "The group of twenty faces reflected ... all the old Moscow." Goncharov notes the artistic completeness and certainty of the play, which was given only to Pushkin and Gogol.

Everything is taken from Moscow living rooms and transferred to a book. The traits of the Famusovs and Molchalins will be in society as long as gossip, idleness and cringing exist.

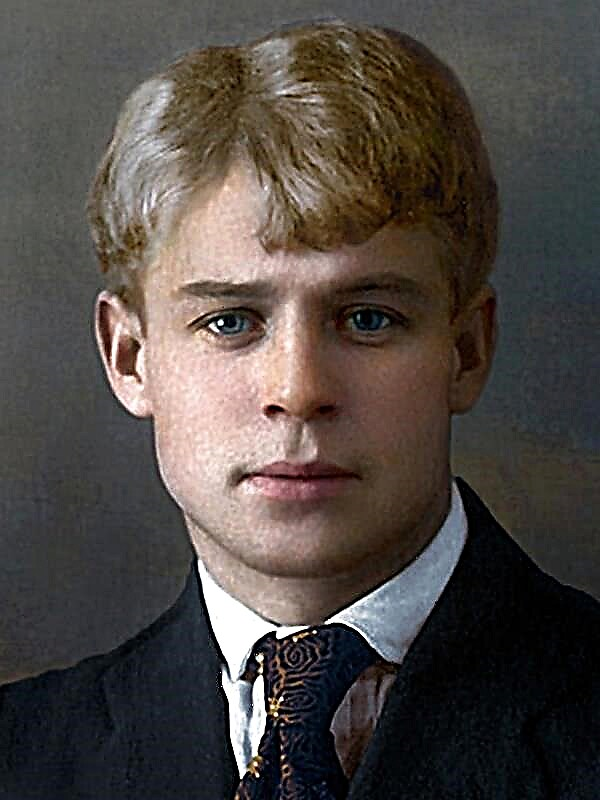

The main role is the role of Chatsky. Griboedov attributed Chatsky’s grief to his mind, “and Pushkin refused him any mind at all.”

Meanwhile, Chatsky as a person is incomparably higher and smarter than Onegin and Pechorin. He is a sincere and ardent worker, and those are parasites ... inscribed with great talents, like painful creatures of an outdated age.

Unlike those incapable of the business of Onegin and Pechorin, Chatsky prepared for serious activity: he studied, read, traveled, but broke up with the ministers for a well-known reason: “I would be glad to serve - to be sick of sickness.”

Chatsky’s and Famusov’s disputes reveal the main goal of the comedy: Chatsky is a supporter of new ideas, he condemns the “past life’s meanest traits” that Famusov stands for.

Two camps were formed, or, on the one hand, the whole camp of the Famusovs and the whole fraternity of “fathers and elders,” on the other, one ardent and courageous fighter, “enemy of searches.”

The love affair also develops in the play. Sophia’s swoon after Molchalin’s fall from the horse helps Chatsky to almost guess the cause. Losing his "mind", he will directly attack the opponent, although it is already obvious that Sofya, in her own words, is sweeter than the "others". Chatsky is ready to beg for what cannot be begged - love. In his praying tone, a complaint and reproaches are heard:

But is there that passion in him?

That feeling? Is it hotness?

So that, besides you, he has a whole world

It seemed dust and vanity?

The farther, the more audible the tears in Chatsky’s speech, Goncharov believes, but "the remnants of the mind save him from useless humiliation." Sophia herself almost betrays herself, saying about Molchalin that "God brought us together." But she is saved by the insignificance of Molchalin. She draws Chatsky his portrait, not noticing that he goes vulgar:

Look, he acquired the friendship of all in the house;

With the priest, he serves three years,

He often gets angry

And he will disarm him in silence ...

... from the old people do not step beyond the threshold ...

... Aliens and at random does not cut, -

That's why I love him.

Chatsky consoles himself after each praise to Molchalin: "She does not respect him," "She does not pennile him," "Shalit, she does not love him."

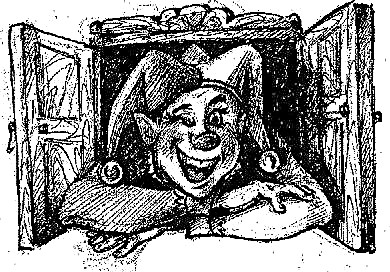

Another brisk comedy plunges Chatsky into the abyss of Moscow life. This is the Gorichevs - the descending gentleman, “husband-boy, husband-servant, the ideal of Moscow husbands”, under the shoe of his cloying cutesy wife, this is Khlestova, “the remainder of the Catherine’s age, with a pug and a girl-boy”, “ruin of the past” Prince Peter Ilyich , a clear fraudster Zagoretsky, and "these NN, and all their sense, and all the content that occupies them!"

With caustic remarks and sarcasm, Chatsky sets them all against himself.He hopes to find sympathy with Sophia, unaware of a conspiracy against him in the enemy camp.

"Million torment" and "grief!" - that’s what he reaped for everything that he managed to sow. Until now, he was invincible: his mind mercilessly hit the sore spots of enemies.

But the struggle tired him. He is sad, bile and picky, the author observes, Chatsky falls almost into a sober speech and confirms the rumor spread by Sophia about his madness.

Pushkin probably denied Chatsky's mind because of the last scene of Act 4: neither Onegin nor Pechorin would have acted like Chatsky in the hallway. He is not a lion, not a dandy, does not know how and does not want to be drawn, he is sincere, so his mind has betrayed him - he has done such trifles! Looking at the meeting between Sophia and Molchalin, he played the role of Othello, to which he had no right. Goncharov notes that Chatsky rebukes Sophia that she “lured him with hope”, but she only did what repelled him.

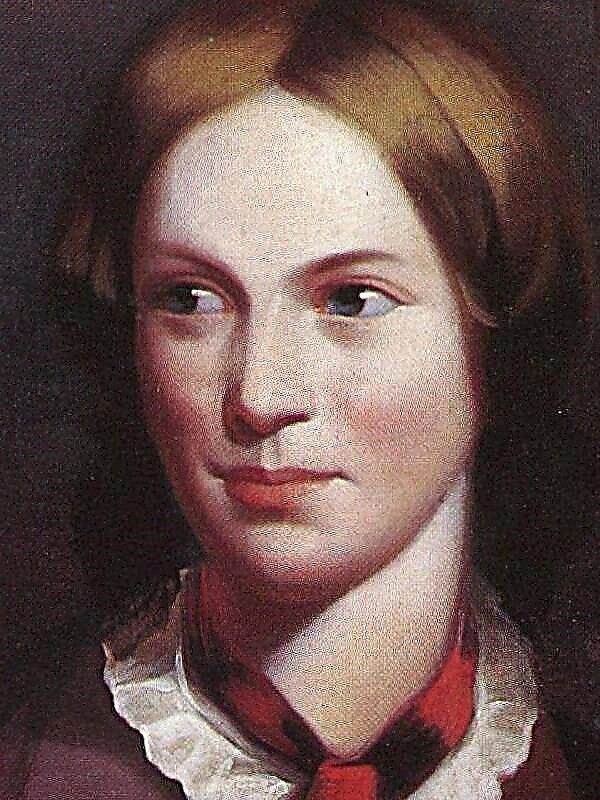

Meanwhile, Sofya Pavlovna is not individually immoral: she sins with the sin of ignorance, blindness, in which everyone lived ...

To convey the general meaning of conditional morality, Goncharov cites the couplet of Pushkin:

Light does not punish delusions

But secrets require for them!

The author observes that Sophia would never have seen from this conditional morality without Chatsky, "for lack of chance." But she cannot respect him: Chatsky is her eternal "reproaching witness", he opened her eyes to the true face of Molchalin. Sophia is “a mixture of good instincts with a lie, a living mind with the absence of any hint of ideas and beliefs, ... mental and moral blindness ...” But this belongs to upbringing, in her own personality there is something “hot, tender, even dreamy”.

Women learned only to imagine and feel, and did not learn to think and know.

Goncharov notes that in Sophia’s feeling for Molchalin there is something sincere that resembles Pushkin’s Tatyana. “The difference between them is made by the Moscow imprint.” Sophia is also ready to give herself out in love; she does not find it reprehensible to start the novel first, just like Tatyana. In Sofya Pavlovna there are makings of a remarkable nature, it was not without reason that Chatsky loved her. But Sophia was attracted to help the poor creature, to exalt him to himself, and then to rule over him, "to make him happy and to have an eternal slave in him."

Chatsky, the author of the article says, only sows, and others reap, his suffering is in the hopelessness of success. A million torment is the crown of thorns of Chatsky - torment from everything: from the mind, and even more from an insulted feeling. Neither Onegin nor Pechorin are suitable for this role. Even after the murder of Lensky, Onegin takes with him to the "dime" torment! Chatsky is different:

He demands a place and freedom for his life: he asks for deeds, but does not want to be served, and stigmatizes cronyism and buffoonery.

The idea of a “free life” is freedom from all the chains of slavery that bound society. Famusov and others internally agree with Chatsky, but the struggle for existence does not allow them to yield.

He is the eternal exposer of lies hidden in the proverb: "Alone in the field is not a warrior." No, a warrior, if he is Chatsky, and at the same time a winner, but an advanced warrior, shooter and always a victim.

This image is unlikely to age. According to Goncharov, Chatsky is the most living person as a person and performer of the role entrusted to him by Griboedov.

... The Chatsky live and are not translated in society, repeating at every step, in every house, where the old and the young coexist under the same roof ... Every business that needs to be renewed causes Chatsky's shadow ...

“The two comedies seem to be nested one into the other”: a petty, intrigue of love, and a private one, which is played out in a big battle.

Further, Goncharov talks about staging the play on stage. He believes that in the game it is impossible to claim historical fidelity, since “the living track has almost disappeared, and the historical distance is still close. The artist needs to resort to creativity, to the creation of ideals, according to the degree of his understanding of the era and the work of Griboedov. " This is the first stage condition. The second is the artistic performance of the language:

An actor, as a musician, is obliged ... to think of that sound of voice and the intonation with which each verse should be pronounced: it means - think of a subtle critical understanding of all poetry ...

“Where, if not from the stage, can one wish to hear an exemplary reading of exemplary works?” It is precisely the loss of literary performance that the public rightly complains.

Metamorphoses

Metamorphoses